Bronchogenic tissue and clusters of pancreatic (clusters of pink cells) are evident in this teratoma.

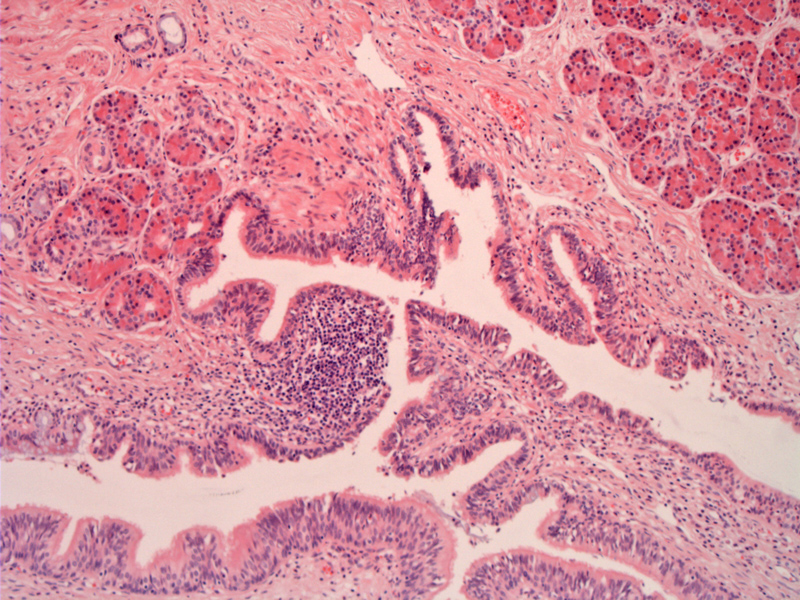

Another image demonstrates mucin producing respiratory-type epithelium and pancreatic acinar tissue. The latter is quite common in mediastinal teratoma.

A different case is devoid of epithelium but contains a hair shaft. The lining is replaces by a brisk lymphohistocytic infiltrate and there is debris in the lumen.

The corresponding resection shows a large central cystic space with hair in the lumen.

The mediastinum is the most common extragonadal location for germ cell tumors (GCT). About 5-10% of all germ cell tumors are found in the mediastinum. Furthermore, primary GCTs comprise up to 20% of all mediastinal tumors. Teratomas are most common (44%), followed by seminomas (37%).1,2

The anterior mediastinum is the commonest site for intrathoracic teratoma. Teratomas consist of tissue from at least two of the three primitive germ layers (although monodermal teratomas have been described). The majority of mediastinal teratomas are mature teratomas that are histologically benign. If a teratoma contains neuroepithelial elements, it is regarded as immature and malignant. In children, the prognosis is quite favorable, but it can often recur or metastasize.

Interestingly, while pancreatic tissue is quite rare in gonadal teratomas, it is commonly found in mediastinal teratomas. Furthermore, compared to gonadal teratomas, medistinal teratomas are more likely to be associated with a malignant component such as a malignant GCT (seminoma, yolk sac tumor or embryonal carcinoma) or a somatic malignancy (sarcoma, carcinoma).1

It must be noted that occasionally, mediastinal GCTs including teratomas are associated with hematologic malignancies such as acute myelogenous leukemia. This is not due to chemotherapy or radiation of the mediastinal tumor. In fact, shared chromosomal abnormalities between the GCT and the hematologic malignancy suggests that they share a common origin, possibly a pluripotent precursor cell in the GCT.1,2

Mediastinal GCTs occur only in males with the exception of medistinal teratomas, which affect both genders equally. Note that prior to puberty, mediastinal GCTs are predominately teratomas or yolk sac tumors, however, after puberty, all types of GCTs are seen.1

These can arise in any age, and the most common range is 20-40 years. Most are asymptomatic. If symptomatic, like other mediastinal masses, presenting symptoms include cough, dyspnea, and chest pain. Rarely, digestive enzymes secreted by intestinal mucosa or pancreatic tissue found in the teratoma can lead to the rupture of the bronchi, pleura, pericardium, or lung. A thankfully rare presentation is trichophysis (coughing up of hair) due to development of hair in a mature teratoma.1

On chest XRay, teratomas are well-defined, round, or lobulated masses, and up to 26% are calcified. These tumors typically are midline or paraxial.

Surgical resection. The tumor may be adherent to adjacent structures, necessitating resection of the pericardium, pleura, or lung.

For mature teratomas, there is excellent long-term cure with little chance of recurrence with complete resection. When complete resection is impossible, partial resection still usually leads to symptom relief, frequently without relapse.

For teratomas with a malignant GCT component or somatic-type carcinoma, the survival rate drops to 50%. For teratomas with a somatic-type sarcoma component, the outlook is dismal as 80% of patients die within 2 years. These tumors would be labled "mature teratoma with carcinomatous or sarcomatous transformation".1,2

• Epithelial : Bronchogenic Cyst

• Mediastinum : Yolk Sac Tumor

1 Fletcher CDM, ed. Diagnostic Histopathology of Tumors. 3rd Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007: 1340-2.

2 Mills SE, ed. Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincoott Williams & Wilkins; 2009: 1126-7.