Case 1: Ruptured ducts can incite secondary granulomatous inflammation as seen here.

Case 2: A more fulminant case shows necrotizing pallisading granulomas in a back-to-back distribution. This example is related to prior TURP.

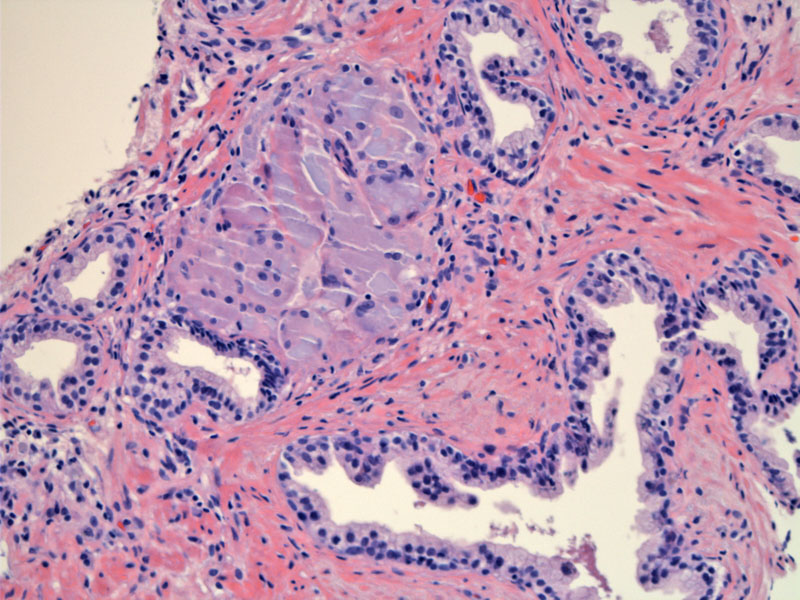

Case 3: This patient had intravesical BCG therapy and caseating granulomas were present diffusely in his prostate.

Another view of these impressive granulomas. BCG induced granulomas can be caseating or noncaseating.

Epithelioid cells, lymphocytes and multinucleated giant cells pallisade at the border of the central caseation.

Case 4: This patient formed granulomas that form the bladder wall after BCG therapy.

Compared to case 3, these granulomas are well-formed, but less impressive compared to the granulomas in the prostate. This is usually the case with intravesical BCG therapy.

Granulomatous prostatitis is important mainly in its ability to mimic prostate cancer clinically, with an abnormal digital rectal exam and elevated PSA. Classification is etiologically based, and is separated into cases which are non-infectious related, vs those with a specific or infectious agent.

Examples of specific etiologies include urinary tract infection, TURP/open prostatectomy, needle biopsy and instillation of BCG into the bladder. Granulomatous prostatiis is a common finding after intravesical BCG therapy. In a review of 12 patients who received intravesical BCG therapy and a subsequent prostatectomy, 9 patients (75%) had granulomatous prostatis (LaFontaine). Interestingly, the granulomas elicited from BCG therapy are usually much more impressive in the prostate than the granulomas seen in the bladder wall.

The infectious organism identified most often is Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Some studies suggest an association between HLA-DRB1*1501, which has been associated with other autoimmune diseases. In many cases, the etiology is unknown and thus, is designated as "nonspecific granulomatous prostatitis".

The granulomas in BCG therapy are indistinguishable from granulomas due to TB infection, which makes sense since they are both mycobacteria introduced into the prostate.

Antibiotics should be given for documented UTI. In cases of mycobacterial infection,anti-tuberculous therapy comprised of the triple drug regimen of rifampicin, ethambutol and isonaizid for 6 months is necessary About 10% of cases can be refractory to conservative management and will eventually need a prostatectomy.

The natural history is that of slow but complete resolution-- up to 62% of patients have spontaneous resolution.

LaFontaine PD, Middleman BR, Graham SD Jr, Sanders WH. Incidence of granulomatous prostatitis and acid-fast bacilli after intravesical BCG therapy. Urology. 1997 Mar;49(3):363-6.

Uzoh CC, Uff JS, Okeke AA. Granulomatous prostatitis. BJU Int. 2007 Mar;99(3):510-2.