Endoscopically, the mucosa is intact but shows edema and subepithelial hemorrhage, most prominent at 12:00. erythema is present along with marked submucosal edema. There is also some mucosal exudate (whitish areas).

Acute hemorrhage and loss of superficial mucosal integrity but with sparing of the deeper portions is typical of an acute ischemic etiology.

An ulcerated area with a pseudomembrane is seen; the area near the splenic flexure is a common area for this to occur due to its watershed nature.

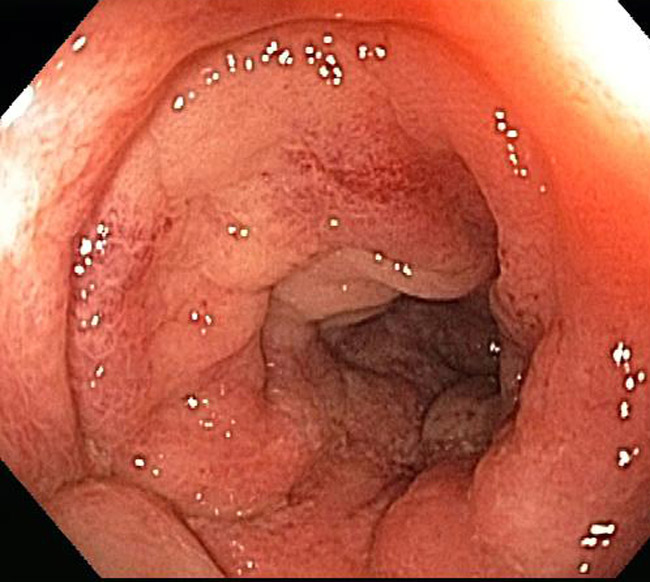

Another case shows an endoscopic image notable for marked mucosal wall edema and a exudate overlying the surface

Exudate is seen in the bottom right. Ulceration is present near 11:00 and marked irregularity to the mucosal surface

The biopsy contains numerous fragments of fibrinopurulent exudate.

The glands shows disruption with an eruption of the material out into the lumen. This image resembles pseudomembranous colitis of infectious etiology.

Vascular wall thickening, interstitial hemorrhage, and withering crypts are seen.

The changes show marked vascular wall thickening.

Etiologies range from vascular occlusion or thrombosis to low cardiac output states. In addition, many drugs can be associated with acute ischemia -- ceratin antibiotics, appetite suppressants, chemotherapeutic agents, pseudoephedrine, cardiac glucosides, diuretics, ergot alkaloids, hormonal therapies, statins, illicit drugs such as cocain, immunosuppressive agents, laxatives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, psychotropic medications, serotonin agonists/antagonists and vasopressors. Just to name a few. The toxin produced from enterohemorrhagic strains of E. coli can elicit microthrombi and also induce ischemia. Vasculitis and sickle cell are rare yet may also be to blame.

The clinical presentation is varied, but one more typical scenerio is the rapid onset of mild abdominal pain and tenderness over the affected bowel, followed by a mild amount of hematochezia within a day of the onset of pain. It frequently occurs in elderly patients with diffuse disease in small segmental vessels and other co-morbidities. Approximately 90% of cases arise in patients over 60 years of age although younger patients may also be affected (Theodoropoulou). Fever is unusual but often the white cell count is elevated.

Most cases are minimal and do not require any specific treatment. Mild cases can be managed with liquid diet and antibiotics. Severe cases require hospitalization and possibly surgical resection of the involved segments. Antibiotics are administered to cover aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and minimize bacterial translocation and sepsis, shown to occur with the loss of mucosal integrity

Many cases are transient and resolve without issue (and often not diagnosed). Potential complications may include bowel perforation, peritonitis, persistent bleeding, protein-losing colopathy, and strictures.

• Small Intestines : Enteritis necroticans (Pigbel)

Theodoropoulou A, Koutroubakis IE. Ischemic colitis: clinical practice in diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 Dec 28;14(48):7302-8.