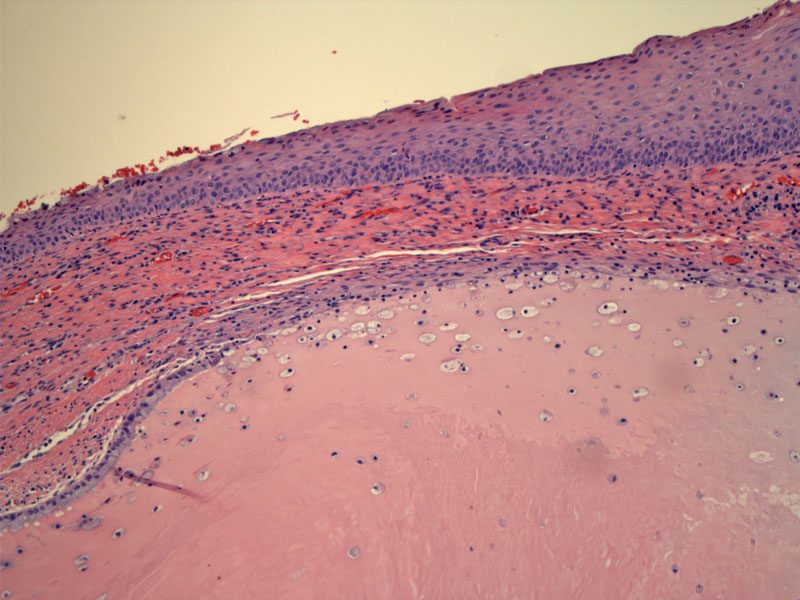

The transformation zone is seen here with metaplastic squamous epithelium overlying endocervical glands. The original squamous epithelium does not overlap endocervical glands, so if you see squamous epithelium above endocervical glands, you can be fairly certain that the squamous epithelium is metaplastic, even if the squamous epithelium is glycogenated and mature.

Metaplastic squamous epithelium underlying a single layer of endocervical epithelium can be appreciated. Remnant strips of endocervical cells at the surface are very helpful in identifying squamous metaplasia, but they are not always present.

Squamous metaplasia is beginning to extend down into an endocervical gland.

Squamous metaplasia is the process by which squamous epithelium replaces endocervical mucinous epithelium at the transformation zone of the cervix. Squamous epithelium is tougher and more resistant than the more delicate columnar cells of endocervical glands. It is thought that the acidic environment of the vagina activates reserve cells located in the basal layer of endocervical glands and thus, initiates the metaplastic process.

Initially, a row of reserve cells populate the basal layer of the endocervical epithelium. These reserve cells proliferate and form multiple layers. The columnar cells may remain as an intact layer overlying the proliferating reserve cells or as fragmented strips of mucinous epithelium that eventually will be exfoliated. As the process continues, the endocervical epithelium is gradually replaced by stratified layers of rounded cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. The orientation of cells appear somewhat jumbled and lack surface maturation. It is at this stage of squamous metaplasia, termed immature squamous metaplasia that is often confused with dysplasia by the novice pathologist.

Helpful features to identify immature squamous metaplasia include: (1) regular monomorphic nuclei with a single prominent nucleoli; (2) rare mitotic figures and never abnormal mitotic figures; (3) occasionally a strip of overlying mucinous epithelium. In contrast, dysplasia is comprised of pleomorphic and hyperchromatic nuclei as well as frequent and abnormal figures.1

Eventually, immature squamous metaplastic epithelium acquires glyogen and becomes virtually indistinguishable from mature squamous epithelium. Squamous metaplasia most often affects the surface mucinous epithelium, however, it may extend down into the crypts and mimic invasive carcinoma. The clinical significance of squamous metaplasia lies in the pathologist recognizing this entity and not overdiagnosing the finding as dysplastic or neoplastic. The finding of squamous metaplasia also tells the pathologist that the clinician has appropriately sampled the transformation zone. Biomarkers such as p16 and possibly Ki-67 may be helpful adjuncts in difficult cases.

Squamous metaplasia occurs more prominently during adolescent years and pregnancy. The process can be arrested and squamous metaplasia is not reversible, therefore, immature squamous epithelium can commonly be found in adult women of all ages and even in post-menopausal woman. As the transformation zone regresses at menopause, the squamous metaplastic epithelium may migrate up into the endocervical canal.1

→Benign squamous metaplasia is important to distinguish from dysplasia.

1 Robboy SJ, Anderson MC, Russell P. Pathology of the Female Reproductive Tract. London, UK: Churchill Livingstone; 2002: 113-5.