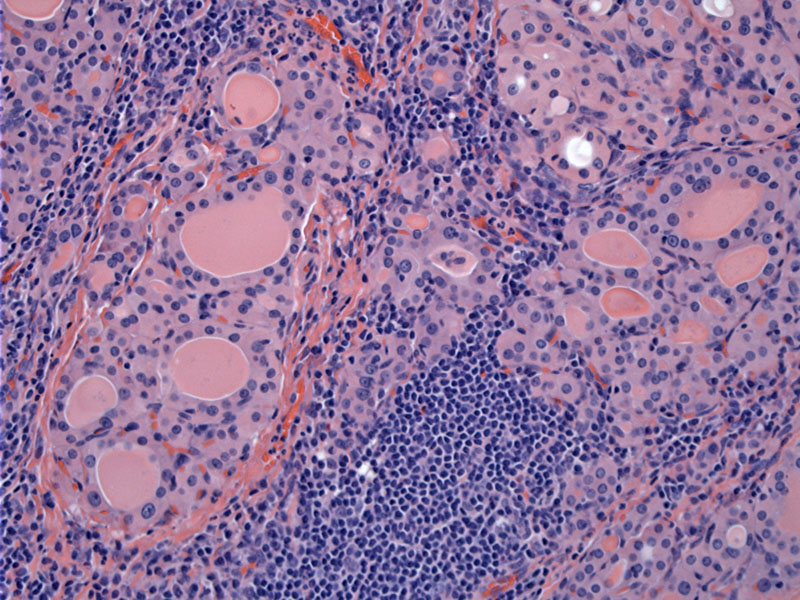

Two features define Hashimoto thyroiditis: lymphoid infiltration (often with germinal center formation) and follicles with oncocytic (Hurthle) metaplasia.

A well developed germinal center is seen here with some adjacent acinar atrophy and oncocytic metaplasia of epithelium.

Nodules composed of follicles lined by oncocytic epithelium can be appreciated here.

Size variability and nuclear atypia are common findings. Scattered epithelial cells with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei are expected findings and should not elicit a malignant or atypical diagnosis.

Another area shows an enlarged nucleus in an oncocytic cell consistent with endocrine atypia.

Atrophy of glands with perifollicular fibrosis may also be seen in this condition. If the fibrosis is prominent and not merely focal AND broad confluent areas of fibrosis is seen, consider the fibrous variant of Hashimoto's (described below).

In addition to the Hurthle cells, there are numerous lymphocytes present in the background. Colloid is lacking.

The aspirate is often cellular and contains groups of follicular cells with Hurthle cell changes. Note the abundant granular cytoplasm and some variation in nuclear size and shape.

The nuclei of Hurthle cells can look large and hyperchromatic, or optically clear and overlapping. In the latter case, these nuclear features can mimic papillary carcinoma (with clear and overlapping nuclei), so beware!

Another image of crowded oncocytic epithelium is surrounded by a dense population of lymphocytes. There is clearly effacement of follicular epithelium in this instance.

The fibrosing variant shows marked follicular atrophy and effacement of the architecture by broad bands of stromal sclerosis. This variant (approximately 10% of cases) is typically associated with marked hypothyroidism, an older age group with a symptomatic, often rapidly enlarger goiter requiring surgical excision to relieve compression.1 . Unlike Reidel thyroiditis, there is no extrathyroidal extension of fibrosis.

Autoimmune thyroiditis occurs when autoantibodies to thyroid constituents such as thyroglobulin and follicular cell antigens lead gland inflammation, dysfunction and damage. It is incompletely understood but appears to be mediated by both cell-mediated and humoral means. The two main entities that fall under the category of autoimmune thyroiditis are Hashimoto thyroiditis and Graves disease. Riedel thyroiditis is a less common member of this group.

Lymphocytic infiltration of the thyroid gland is the common to both Hashimoto (and its variants) and Graves disease. It is the morphology of the intervening follicles that determines whether an entity should be called Hashimoto or Graves. In Hashimoto thyroiditis, the follicular cells show prominent oncocytic (Hurthle-cell change) along with atrophy of follicles. In Graves disease, the follicles are hyperplastic.2,3

It is also interesting to note that Graves and Hashimoto disease may lie on a continuum, and one condition may evolve into another. For example, the hyperactivity of Graves may lead to gland exhaustion and atrophy, evolving into Hashimoto. There are rare examples of the reverse sequence, where Hashimoto evolves into Graves. Additionally, there are instances where patients demonstrate features of both Hashimoto and Graves concurrently.2

Hashimoto thyroiditis can coexist with other autoimmune conditions such as diabetes, pernicious anemia, diabetes, Addison disease and Sjogren syndrome. Hashimoto thyroiditis and lymphocytic adrenalitis (lymphocytic infiltrative of the adrenal gland leading to hypoadrenalism) is known as Schmidt syndrome.2

Several variants of Hashimoto's thyroiditis have been described.

- The fibrous variant typically occurs in an older population, and presents with a markedly enlarged symptomatic goiter that compresses surrounding structures. Surgery is often necessary to relieve this pressure. Hypothyroidism may be significant. Microscopically, the gland is demonstrates areas of confluent fibrosis, as well as marked perifollicular fibrosis, which may entrap atrophic follicles and mimic carcinoma.

- The juvenile variant occurs in younger patients. Follicle atrophy is not common, but a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and Hurthle cell change is present. This entity remains ill-defined, however, with limited histological correlation.

A note on confusing terminology: Some authors use the terms lymphocytic and Hashimoto's thyroiditis synonymously. Some authors use the term lymphocytic thyroiditis to describe the juvenile variant of the Hashimoto thyroiditis. This can be very confusing, but reading the text carefully should tell what the author is referring to when the very vague term "lymphocytic thryoiditis" is used.

Hashimoto Thyroiditis: Generally diagnosed after age 40 with a female predilection F:M ratio of 6:1. Presents with goiter and/or hypothyroidism. The thyroid gland is typically symmetrically enlarged, with a firm bosselated surface. Serological testing would demonstrate autoantibodies to thyroid peroxidase (an enzyme involved in the production of thyroid hormone), thyroglobulin (a protein produced by thyroid epithelial cells) and thyrotropin receptors (binds TSH).

Lymphocytic thyroiditis: More common in children and adolescents, referred to as the "juvenile" form of autoimmune thyroiditis. Presents with asymptomatic goiter and may be associated with transient hyperthyroidism; patients often have a strong family history of thyroid disease.3

Treat hypothyroidism with thyroxine. Surgery may be performed at times to relieve compressive symptoms.

Patients generally do well with medical management and surgery. An important complication is the development of thyroid lymphoma, which arises in a setting of Hashimoto thyroiditis. In a study of Japanese women with Hashimoto thyroiditis, 0.1% developed thyroid lymphoma. Although this percentage does not appear to be noteworthy, it is 80 times higher than expected of the control population.1

1 Lloyd RV, Douglas BR, Young WF Jr. Endocrine Diseases: Atlas of Nontumor Pathology. First series, Fascicle 1. Washington DC: AFIP; 2001: pg 115-126.

2 Rosai, J. Rosai and Ackerman's Surgical Pathology. 9th Ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2004: 520-3.

3 Thomspon LDR. Endocrine Pathology: Foundations in Diagnostic Pathology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2006: 20-8.